Understanding Cultural Competency

April 6, 2021 | By

The term cultural competence describes a set of skills, values and principles that acknowledge, respect and contribute to effective interactions between individuals and the various cultural and ethnic groups they come in contact with at work and in their personal lives.

A good understanding of cultural competency has become essential for anyone who plans to work in human services. It’s important enough that even the American Psychological Association now lists it as one of the core competencies for psychology professionals today.

Connecting with other people in a meaningful way and relating to them on a human level without judgement is key to any aspect of human services work. And becoming culturally competent is the only way to do that.

The concept of cultural competency even recognizes that the way we communicate and express empathy are influenced by the culture we live in, so even the act of empathizing does not always translate to other cultures in the exact same way.

Cultural competency describes the full set of attitudes, communication and listening skills you need to effectively connect with people from other cultures, and it all builds on your natural sense of empathy and connectedness to others.

It takes work to turn your innate compassion into cross-cultural connections. Cultural competence describes the process of doing that work.

A Definition of Cultural Competence

Historical Perspectives on Cultural Competency Definitions in Human Services

Taking Cultural Competence Concepts Beyond Definitions

Even Program Accreditors Have Something to Say About Cultural Competency

Cultural Competence Eventually Leads To Cultural Proficiency

But not everybody in human services is in full agreement about how cultural competence should be defined. You are likely to come across a few different terms in common use, each one having a slightly different orientation and perspective on the topic:

- Cultural safety

- Cultural awareness

- Cultural sensitivity

- Cross-cultural competence

- Transcultural competence

- Multicultural competence

You can see why understanding the concept has to start with a universal definition of what it is.

A Definition of Cultural Competence

Cultural competence is a term that gets thrown around a lot in fields ranging from social justice to literary criticism to healthcare. Even breaking the term down into its individual parts misses some of the nuance of what it’s all about.

Cultural: Of or relating to the customary beliefs, social forms and material traits of a racial, religious or social group

Competence: The quality or state of having sufficient knowledge, judgment, skill or strength (as for a particular duty or in a particular respect)

Chances are you know a lot of people who grew up in a household of immigrants but went to school with you and everybody else in the community, picking up all the local culture along the way. Culture really isn’t fixed in place, it blends with other cultures to form new ones, and changes over time.

No matter how much you might know about the place a person comes from, you can’t really assume you truly understand their culture entirely. And in that reality, can you ever really have sufficient knowledge and judgement to assess a person’s culture? Or is it more likely that you will need to always be learning, always acquiring fresh skills? This is why having an open mind and the ability to take people and groups as they are on a case by case basis is a big part of being culturally competent.

No matter how much you might know about the place a person comes from, you can’t really assume you truly understand their culture entirely. And in that reality, can you ever really have sufficient knowledge and judgement to assess a person’s culture? Or is it more likely that you will need to always be learning, always acquiring fresh skills? This is why having an open mind and the ability to take people and groups as they are on a case by case basis is a big part of being culturally competent.

Not only is cultural competence always a moving target, it’s also a two-way street. Your own cultural background plays a role in how you relate to other cultures, and how people in those cultures relate to you.

There is no single set of knowledge or skills you can pick up that will certify you as being culturally competent. There are thousands of cultures and subcultures in this world, and hundreds of thousands of unique combinations as those cultures merge with each other. Part of being respectful of cultural diversity is realizing that you can’t possibly fully understand them all – no one can.

Defining Cultural Competence In The World of Human Services

Most people in human services today view cultural competence as more of a process than a product.

There are four elements that go into developing cultural competency:

- Awareness – Of your own view of the cultural world

- Attitude – Toward difference between cultures

- Knowledge – Of diverse cultural beliefs, views, and practices

- Skills – In dealing with the differences between different cultures and with their interrelationships

Cultural competency can have different meanings in different contexts. In the field of human services, the applications can depend on the cultural concepts most closely related to the kind of practice you work in. Some examples:

- Psychology – Therapists working with Latino youth have learned to adopt the use of Interpersonal Psychotherapy in their practices after finding it to be a culturally effective treatment because it aligns with Latino values.

- Social Services – At the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center in New York, social workers dealing with medical issues among a largely Chinese immigrant population are particularly careful to get a full history of the use of herbal medicines.

- Counseling – Marriage and family therapists working with Black clients lean on the strengths of Black family culture with new data showing better therapeutic outcomes.

The CDC offers their own cultural competence definition in health and human services work.

“Cultural and linguistic competence is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables effective work in cross-cultural situations.” ~ Centers for Disease Control

This definition was adopted after studies found that racial and ethnic minorities tend to receive a lower standard of care even when controlling for income, wealth, and location factors.

Of course, this is true not just in healthcare, but across the spectrum of human services. And that’s the exact thing that makes cultural competence such an important topic today in the era of racial reconciliation.

Historical Perspectives on Cultural Competency Definitions in Human Services

On a practical level, social workers and other human services professionals have always had to be culturally competent to be able to do their jobs. It’s impossible to build a rapport with individuals or within a community if you don’t have respect and understanding.

But this was not emphasized as a point in human services education until relatively recently. A retrospective study in 2000 found that human diversity issues were only discussed in social work literature in about 8 percent of published articles from 1970 to 1997.

It wasn’t that no one recognized that different cultures might have different standards. Instead, there was just a different perspective on how to handle those differences.

Social services for immigrants in the United States originally focused on assimilation rather than cultural recognition.

In the early years of social services, assimilation was the big thing. America was seen, for good reason, as the world’s melting pot. A big stew of races, cultures, and concepts cooked up a unique mix where everyone celebrates both St. Patrick’s Day and Cinco de Mayo, and Polish kielbasa with German sourcrout is available at every hot dog stand on any street corner in the country.

But the melting pot analogy overshadowed what was being left out, or appropriated without acknowledgement. Not every minority made it into that stew. Social work educators and others focused on trying to wedge Native Americans, African Americans, and Asians into the dominant Western ideological perspective.

By the 1960’s, it was becoming clear that this paternalistic approach was failing. Some threads of multiculturalism started to emerge in human services. By the 1970s, psychologists were exploring why traditional Western psychotherapeutic techniques tended to fail with patients from less verbal cultural backgrounds, such as those from many African nations. The Western traditions built into the entire field of modern psychology were rooted in notions of individualism and structure that weren’t universal in human culture. Treatments based on those concepts weren’t serving other populations well.

In 1982, anthropologist James Green published the book Cultural Awareness in the Human Services, which offered some of the first ethnographic approaches to delivering culturally-aware social services. And in 1989, the term cultural competence was first used and described by Terry Cross, founder of the National Indian Child Welfare Association, co-author of the paper Towards a Culturally Competent System of Care and a member of the Seneca Nation.

The Original Definition of Cultural Competence

“Cultural competence is a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals and enable that system, agency, or those professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations.” ~ Terry Cross et al

But it wasn’t until the 2000’s that the field really came to grips with cultural competency as a practical matter. Cultural competence goes beyond tolerance and diversity to active appreciation and adaptation of non-Western cultures. Moving from a position where other cultures are seen as a stepping-off point for transitioning to a Western lifestyle, to recognizing them as worthy of respect and acceptance in their own right. This has been a key mental leap for modern human services teams.

The Six Points of Cultural Competence As Defined by Terry Cross

Part of the genius of the Terry Cross definition of cultural competence was that it emerged from a continuum of behaviors in response to cultural differences. The six points along the line of cultural competency were defined as:

- Cultural destructiveness – The active attitudes, policies, and practices that destroyed culture. Those included institutions such as the Indian boarding schools and the Chinese Exclusion Laws.

- Cultural incapacity – Systems which treat cultural perspectives with disregard, incorporating the presumption that the majority culture is the only valid one. Without attempting to specifically destroy other cultures, these systems reward cultural dominance through racist or stereotypical policies.

- Cultural blindness – This approach disregards culture, attempting a policy of cultural blindness that in fact simply accepts approaches traditionally accepted in the dominant culture. They may ignore strengths in minority communities and sub-cultures and weigh outcomes against dominant cultural tendencies.

- Cultural pre-competence – Pre-competent approaches recognize differences in cultures and weaknesses in serving minority communities and attempt to correct them. They may hire more minority staff and explore outreach efforts, but fall prey to tokenism and lack of self-assessment.

- Cultural competence – As Cross defined it, a set of behaviors, attitudes, and policies that enable effective performance in cross-cultural situations.

- Cultural proficiency – Finally, proficient approaches hold cultures in high esteem. This involves active pursuit of competency by adding to the knowledge base of cultures and actively seeking out staff with new perspectives and competencies.

That transition was and is a tricky one. There are Western cultural concepts that aren’t going anywhere. A little baksheesh is a very common and culturally-accepted way of greasing the wheels in many global societies, but bribing healthcare workers or officials for preferential treatment in social services is just never a good idea.

There are blurrier lines with more ethical ambiguity than that one, but the point is that human services workers are going to privilege their own cultural background in some situations, no matter how much respect they have for other cultures.

But human services have moved to more of a give and take model, where social workers and others work harder to shift their own expectations and habits than to force changes on the part of clients.

Taking Cultural Competence Concepts Beyond Definitions

Ultimately, cultural competence is defined by actions. How you treat people reveals your respect and awareness.

Something unique about practicing culturally competent human services work is that it means your actions toward individuals of different cultures must also be different.

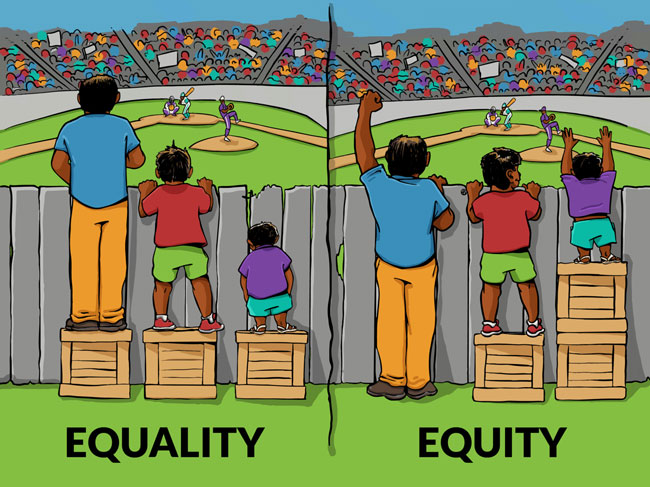

Equality is culturally blind. Culturally competent practitioners aim for equity, instead.

Interaction Institute for Social Change | Artist: Angus Maguire.

Equity is about fairness—approaching every individual with what they need, as individuals. That’s cultural competency in a nutshell: recognizing the person in front of you as a person, not a caricature, not a case file.

How To Be More Culturally Competent

Some culturally competent practices in human services are obvious:

- Have staff who can speak the language of the community or offer easy access to interpreters

- Deliver services at hours and locations that are accessible

- Be considerate of cultural mores and taboos

And some of the ways to achieve those practices are obvious, too:

- Employ diverse and multilingual staff

- Educate staff about the populations they will most commonly be in contact with

In other cases, however, human services pros are dealing with unknown unknowns… things about another culture that you may never even realize you don’t understand. If you are visiting a client who is a recent immigrant from Korea and happen to be taking notes with a red pen, you are probably making them extremely nervous. Tradition there says a person whose name is written in red ink is about to die.

On the other hand, many Western habits and customs strike other cultures as strange… a perverse insistence on schedules, for instance, may have you fuming when your clients keep turning up 15 minutes or more late, but that’s common in much of Asia and Latin America.

Add up all these major and minor violations of cultural norms in the average American urban center and pretty soon you can barely move for fear of offending.

The answer is not to attempt to memorize every possible cultural quirk. Instead, it’s about being open-minded.

Being Culturally Sensitive Doesn’t Mean Pandering

It can also be important to not go overboard. The Charles B. Wang Community Health Center in New York primarily serves a population of recent Chinese immigrants. But despite having a staff who largely speak different Chinese dialects and maintaining an extra awareness of the traditional Chinese herbal remedies that patients may be familiar with, the Center tries not to be too “Chinesey.” Posters and murals around the center are found not just in Chinese and English, but also Korean and Spanish, engaging in some of the cultural diversity for which New York is rightly famed.

Ddmmen, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The Actions of A Culturally Competent Human Services Professional

The APA Individual, Cultural, and Disciplinary Diversity competency has some yardsticks to use for measuring cultural competence. They split the components in two:

- Monitor and apply knowledge of self and others as cultural beings

- Identify the relationship of social and cultural factors in the development of problems

You can break down the process of applying that competency into three steps:

Asking/Listening

Maybe it sounds strange, but competency starts with assuming incompetence. Human services professionals are trained to ask about cultural identities, health beliefs, and history rather than assuming the answers. Offering the opportunity for patients to speak freely and openly without judgement is the only way to be sure you get the information you need for planning treatments or services.

Respect/Awareness

Next, competency requires respect for ideas and perspectives coming from other cultures, even when they are totally unfamiliar or even offensive by your own cultural standards. An open-minded approach is required. A good poker face can be important for human services staff to avoid appearing judgmental. Acceptance of other views is key to cultural competency.

Education

The dynamic nature of cultural competence requires continuing education. You’ll always be learning new things about your community if you are culturally competent. But this also has to start with a foundation of cultural awareness, something that usually happens during college programs that train human service workers.

Fortunately, the human services fields have moved well beyond their rocky introductions to cultural competency. Today, anyone studying human services, or social work, or even healthcare is definitely getting a first-rate education in cultural competency.

Even Program Accreditors Have Something to Say About Cultural Competency

Today, every higher education accrediting agency that deals in human services has strong requirements that all accredited programs include diversity content in their curricula.

Council on Social Work Education – Competency 2: Engage Diversity and Difference in Practice: Requires social workers understand the intersectionality of multiple factors including culture in the identity of clients and apply and communicate their understanding of that complexity. Social workers are required to present themselves as learners and apply self-awareness and self-regulation to manage personal biases.

American Psychological Association Commission on Accreditation – Guiding Principles of Accreditation, Professional Values Standard 2a: Commitment to Cultural and Individual Differences and Diversity: Accredited psychology programs at every level are committed to a broad definition of cultural and individual differences.

The Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs – Core Curriculum Area, Counseling Approaches and Principles C.5.8: Individual empowerment and rights and C.7.6: Ethical, legal, and cultural implications in assessment: Counselors are required to know and analyze the implications of culture and to consider cultural influences when testing and making responsible decisions in patient treatment.

Masters in Psychology and Counseling Accreditation Council – Standard C, Multiculturalism and diversity Part 1: Knowledge and Self-awareness: Programs holding this accreditation must demonstrate that students have knowledge and awareness of themselves and others as shaped by individual and cultural diversity and apply that knowledge in their assessment, treatment, consultation, and all other professional interactions.

Council for Standards in Human Services Education – Standard 8: Fostering the development of culturally competent professionals: This entire standard revolves around demonstrating how accredited programs deliberately include cultural competence training, build it into policies, procedures, and practices, and show how their curriculum develops cultural competence skills in graduates.

Commission on Accreditation for Marriage and Family Therapy Education – Standard 2: Commitment to Diversity and Inclusion: COAMFTE defines specific commitments and student learning outcomes relating to diversity and inclusion including teaching ideas and professional practices. They also specify that the program environment must incorporate safety, respect, and appreciation for students cultural backgrounds, and requires student experience in diverse, marginalized, or underserved communities as a part of the curriculum.

Those are all an excellent start in offering human services professionals a solid education in cultural competence. But there’s one more step to go.

Cultural Competence Eventually Leads To Cultural Proficiency

At this point you’re probably noticing something important about cultural competency. That is, it’s just a starting point.

Cultural competence is invaluable, but it’s also just a step toward a larger goal. Human services professionals in the future need to become more than culturally competent: they need to achieve true cultural proficiency.

Culture is a part of every human being, but it does not define them. Ultimately, human services providers can’t allow cultural blinders to hide the warmth, beauty and individuality of people.

But people expand on culture. Individuals have ideas, dreams and preferences that come from their own unique experiences. Culture isn’t constant and it isn’t fixed. It’s never a substitute for individual thoughts and perspectives.

A Broad Range of Perspectives Leads to Many Different Interpretations

Meredith Minkler, a professor of public health at the University of California in Berkeley, like many human services and healthcare professionals, was accustomed to showing her solitary with the Black Lives Matter movement by taking a knee when asked to stand for the national anthem. The gesture, initiated by San Francisco 49er’s quarterback Colin Kaepernick, had been widely adopted by both Black and white athletes in the wake of violent instances of police brutality and racial inequality in the United States.

But when Minkler did so at a large gathering of public health professionals while standing next to two African American military officers, she was surprised to find herself kneeling alone. Both of the officers stood ramrod straight and facing the flag.

In reviewing the episode with a diverse group of professionals afterward, Minkler found a broad range of perspectives on kneeling for the anthem… as a sign of deference, humility, respect or weakness. There was no consensus. Each individual had their own social experiences that shaped their view. Those from the military, even minorities, were shaped by that experience. Others had their views formed by the religious practice of kneeling in prayer as they had been taught to do growing up.

Interestingly, Kaepernick’s original decision to kneel for his gesture was informed by former Green Beret and pro-football player Nate Boyer, who suggested it would be more respectful than simply sitting during the anthem, as Kaepernick had previously done. Even among veterans, then, there’s no single or simple cultural view to adopt.

Mike Morbeck, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

In some senses, it’s better to think of cultural proficiency as having a constant awareness of your own unawareness of exactly what has gone into the social and psychological makeup of people you work with. Their experiences will have shaped them, as all of ours do. But unless you ask, you can never assume which of those experiences has influenced them the most.

Even your ideas about what may be problematic, offensive, or insensitive to someone from another culture are themselves usually rooted in your own cultural background—not theirs.

Communication is the only way to make the leap to cultural proficiency. Asking an individual what their perspective is offers the ultimate in respect.